Aging populations and the welfare state

Both the US and UK are experiencing demographic shifts:

Declining birth rates: Fertility rates have fallen below replacement level (2.1 children per woman)

Increasing longevity: Life expectancy has risen dramatically in recent decades

Growing dependency ratios: The proportion of retirees to working-age adults is rising steadily

Looking at OWID data, we can see dependency ratios rising from approximately 110 in 2025 to 120 by 2035 for the UK.

This combines with broader economic stagnation to create problems for governments

"A lot of countries basically are caught in a trap from which there is no escape.

4) You get voted out because all of these are immensely unpopular.

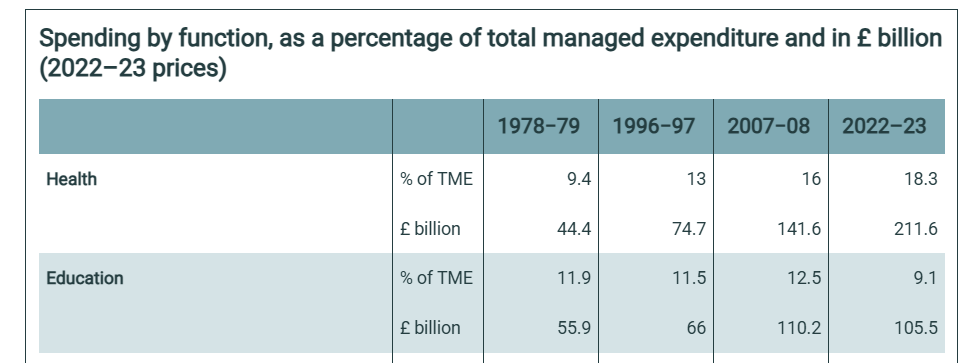

Rising entitlement costs: In both the US and UK, the share of government spending devoted to pensions and healthcare continues to grow

Fiscal pressure: As fewer workers support more retirees, tax burdens increase or deficits expand

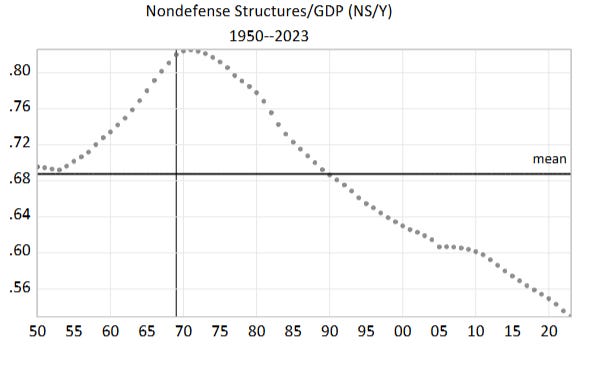

Reduced investment: Resources directed toward consumption by the elderly reduce capital available for future-oriented investments. Supply restrictions on housing turn housing into a nonproductive appreciating retirement asset for the middle class that diverts resources from productive investment (examined in more detail below).

These dynamics interact with democratic processes:

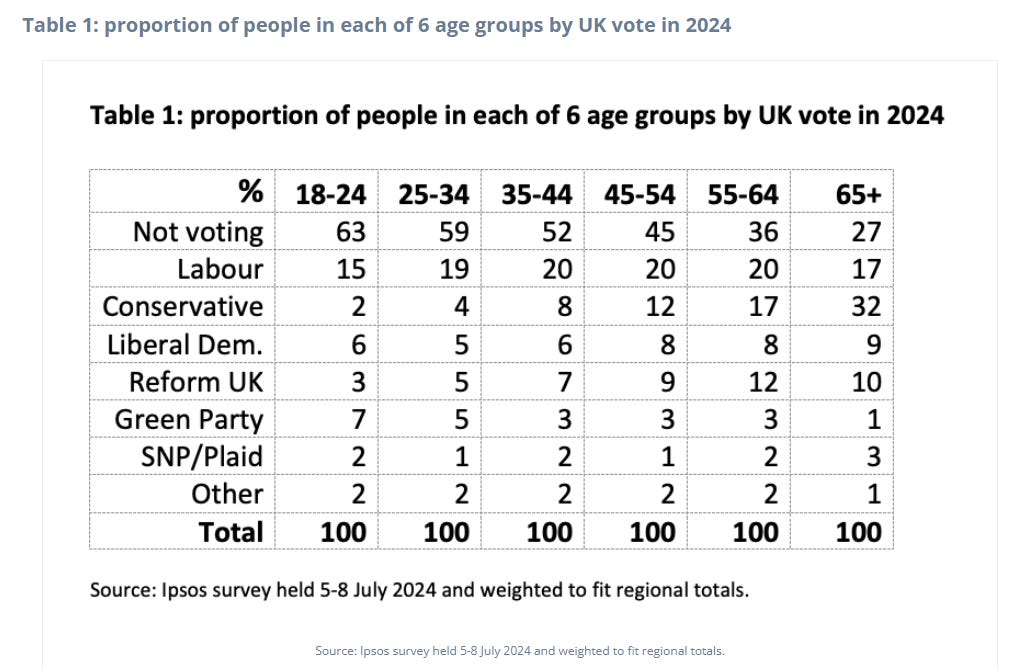

Differential voting rates: Older citizens vote at significantly higher rates than younger ones (as we’ll see below)

The median voter effect: As the electorate ages, the median voter also ages, pushing political parties to cater to older voters

Concentrated interests: Retirees form a powerful voting bloc focused primarily on protecting benefits

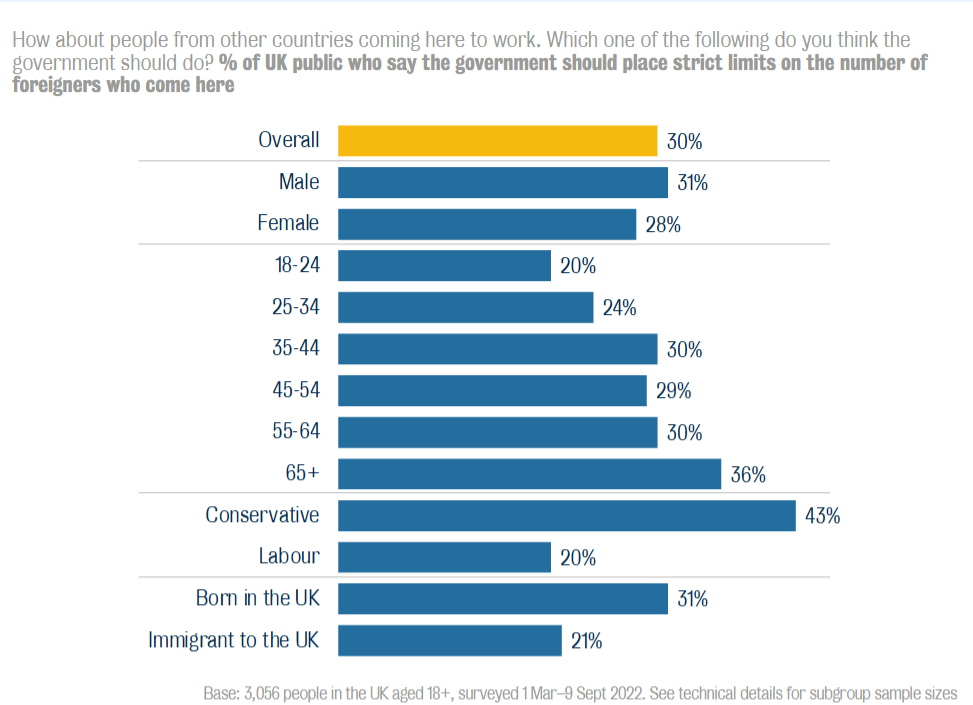

Immigration—particularly of working-age individuals—offers a potential solution to demographic imbalances by improving dependency ratios and increasing the tax base to fund elderly benefits. Yet research shows that elderly voters are often the most opposed to immigration (examined in detail further below).

A study examining this dynamic found:

We investigate the effects of population ageing on immigration policies using a citizen-candidate model of elections. In each period, young people work and pay taxes while old people receive social security payments. Immigrants are all young, meaning they contribute significantly to financing the cost of public services and social security. Among natives, the elderly and the poor benefit the most from public spending. However, since these two types of voters do not internalise the positive fiscal effects of immigration, they have a common interest in supporting candidates who seek to curb immigration and increase the tax burden on high-income individuals. Population ageing increases the size and, in turn, the political power of such sociodemographic groups, resulting in more restrictive immigration policies, a larger public sector, higher tax rates, and lower societal well-being. Calibrating the model to UK data suggests that the magnitude of these effects is large. The implications of this model are shown to be consistent with the patterns observed in UK attitudinal data.

It explains the dynamic further:

Note that the model generates no actual competition between immigrants and natives over welfare benefits because the fiscal gains from immigration always outweigh its crowding-out effect on public services (at a given tax rate). Nevertheless, the political process induces perceived competition. The mechanism is as follows. Pro-immigration candidates propose more immigration, less public spending, and lower taxes than anti-immigration candidates. Because elderly and poor citizens are almost unaffected by a drop in the tax rate but are strongly harmed by spending cuts, the policy platform of a pro-immigration candidate – if implemented – produces a negative short-term fiscal effect on these sociodemographic groups relative to that of an anti-immigration candidate. This prompts elderly and poor voters to behave as though they are competing with immigrants over public benefits. That is, even if they benefit the most from public spending financed through immigration, they support relatively anti-immigration candidates in the elections on the grounds of the negative fiscal effects of pro-immigration policy platforms, in line with the stylised facts.

Demographic shocks tilt the relative power of the two opposing political factions. Specifically, population ageing results in a larger share of elderly voters, fuelling support for anti-immigration candidates. This yields an equilibrium policy of low immigration and high public spending. This mechanism underpins the main analytical results of this paper, which are as follows:

1.

A rise in longevity and/or a fall in the birth rate increases the share of elderly voters, determining the electoral success of a relatively anti-immigration politician.

2.

The election of an anti-immigration politician leads to a tightening of immigration policy, an increase in public spending, and a sharp rise in the tax rate. Hence, the political process tends to exacerbate the effects of population ageing on public finances.

3.

If immigrants have higher fertility rates than natives, a reduction in the immigration flow due to the policy change lowers the country’s birth rate, causing further population ageing and an even tighter immigration policy in the following period.

4.

The tightening of immigration policy generates a welfare loss for the entire society, although it mostly harms middle- and high-income workers as well as future generations.

Note that other research finds that anti-immigration attitudes are more a function birth cohort/year than age independently:

Using household surveys for 25 countries over a 12-year period, this paper investigates why the elderly are more averse to open immigration policies than their younger peers. We find that the negative correlation between age and pro-immigration attitudes is mostly explained by a cohort or generational change. In fact, once we control for year of birth, the correlation between age and pro-immigration attitudes is either positive or zero in most of the countries of our sample. Under certain assumptions, our estimates suggest that aging societies will tend to become less averse to open immigration regimes over time.

And other research finds that this is partly due the younger cohorts being better educated

But at the same time the picture is dominated by another even more powerful inter-cohort change, namely the fact that younger cohorts are better educated, and that higher education is a highly significant factor leading to more tolerance. Hence, the main political message to be derived from this analysis is that continued strong investments in education of the young cohorts is the best remedy against the otherwise prevalent tendency of increasing intolerance among young cohorts. Or viewed the other way around, should education levels stagnate or even deteriorate for the younger cohorts that may imply a future decline in tolerance towards immigration.

(Older voters tend to hold more culturally conservative views across a range of issues.

As populations age, this could shift the overall political center of gravity toward more culturally conservative positions, even as younger generations become more progressive.)

Case Study: UK's Triple Lock and NHS

The UK provides a clear example of this dynamic in action:

The "triple lock" ensures state pensions rise by whichever is highest: inflation, average wage growth, or 2.5%

NHS spending increasingly focuses on conditions affecting the elderly, while mental health services (which disproportionately benefit younger people) funding is flat in real terms

Finally, spending conducive to economic growth is often neglected. For example, funding for UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), the country’s largest public funder of research, has not increased, representing a cut in real terms

Case Study: US Social Security and Medicare vs. Education

In the US, we see similar patterns:

Social Security and Medicare enjoy robust political protection despite fiscal challenges

Congress regularly finds ways to defer difficult decisions on entitlement reform

Meanwhile, education spending and especially infrastructure investment—which primarily benefit future generations—face consistent budgetary pressure

The Political Quadrilemma

Policymakers face four options, all politically toxic:

Cut elderly benefits: Political suicide given voting patterns : the elderly vote at much higher rates and are an increasing share of the population as we saw earlier

Dramatically raise taxes on workers: Creates political backlash from workers

Increase immigration: Often politically unpopular, especially among older voters

Drastically cut other government spending: Creates different political problems, like slower growth down the line

Digression: Raising fertility rates

A fifth option—increasing fertility rates—might seem promising but faces significant challenges. Research on interventions like the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit suggests mixed results.

Another study of Russia's "Maternity Capital" program showed positive effects on fertility but at substantial cost—approximately $50,000 per additional birth.

However a child allowance could still generate substantial benefits overall : another study found that “[making the Child Tax Credit expansion in the American Rescue Plan permanent] would cost $97 billion per year and generate social benefits with net present value of $982 billion per year. Sensitivity analyses indicate that our estimates are robust to alternative assumptions and that all three child allowance policies we evaluate produce very high net returns for the U.S. population.”

Further, improvements in fertility technology could also enable more women to have children when and if they want to.

Automation and AI: Technology that significantly enhances productivity in healthcare and eldercare could reduce the resource burden. However robotics is hard and that would bottleneck productivity gain in eg eldercare to the extent it requires physical assistance.

Left-leaning parties that might traditionally favor social spending find themselves defending elderly benefits at the expense of investments in children, education, and infrastructure. Right-leaning parties that might favor fiscal responsibility struggle to propose realistic entitlement reforms without alienating their often older voter base.

Democracy, the median voter and the middle class

Democratic systems operating under majority rule tend to align with the preferences of the median voter. The median voter theorem suggests that when voting depends primarily on preferences along a single dimension (like economic policy), political competition drives parties toward positions that appeal to voters in the middle of the distribution.

Responding to influential work by Gilens and Page suggesting that economic elites dominate policy outcomes, subsequent analysis in 2016 found that "strong support from the middle class is about as good a predictor of a policy being adopted as strong support from the rich." The research found that "change is enacted 47 percent of the time that median-income Americans favor it at a rate of 80 percent or more," compared to 52 percent when elites favor it at similar rates.

In practice, this means democratic outcomes often reflect middle-class interests rather than those of either the poorest or wealthiest citizens. While the very wealthy may exercise outsized influence through campaign contributions and lobbying, many policy deadlocks arise from middle-class voters protecting their advantages.

(A notable exception is the degree of government redistribution in a wider cross-country context, where the “preferences of the lower socioeconomic group, rather than those of the median or upper strata, are most predictive of realized redistribution”

The study notes that “…the U.S. setting may not be reflective of policy deliberation more generally — for example, the specifics of American politics may make it particularly susceptible to the influence of the affluent relative to other democratic countries.” )

The Case of Elon Musk

One of the most visible instances of the influence of the ultra-wealthy on politics is Elon Musk. Elon Musk spent over $290 million backing Donald Trump’s successful 2024 campaign, making him the top individual donor. His funding—channeled through a super PAC—played a pivotal role in mobilizing turnout in key swing states. While broader political trends favored Trump, Musk’s contribution likely shifted the margin in several decisive areas. For example the Guardian reports comments by the Trump campaign’s political director:

“By conserving hard dollars, we were able to go wider and deeper on paid voter contact and advertising programs,” Blair said. That, he added, included broad ad campaigns aimed at a national audience, as well as – critically – more targeted campaigns directed at Black and Latino men.

This seems to have had an effect, based on post-vote surveys

Perhaps a better model of the problematic influence of the ultra-wealthy on politics is as a tail-risk : typically not decisive on many everyday issues, but much more influential on certain rare instances, and focused on high-leverage events like presidential elections. It would be much harder for the wealthy to achieve the same sort of leverage with appointments of UK prime ministers for example.

Why it would be harder for the wealthy to achieve similar influence on UK PMs

In the UK MPs in each party vote to narrow down candidates for party leader, then the party’s general membership votes to select the party leader from those options. Finally the leader of the party or coalition that wins a majority of votes becomes the prime minister. The party leader can be changed mid-term. If a PM loses a no-confidence vote by the House of Commons (or by the party, since that almost always triggers a similar vote by the House), a new party leader is chosen by the previously described procedure and they become the new PM. All of this means that there’s no easy source of high leverage like US swing states (the process dilutes the leverage from marginal constituencies) and PMs can be quickly removed (as seen with Liz Truss or Boris Johnson).

Further there are effective limits on campaign spending by parties and by other organizations. As the Institute for Government explains:

At the 2024 general election, a party standing in all 632 seats in Great Britain was able to spend just over £46m during the regulated period. This limit consisted of £34m of party spending, and an average of £19,000 per candidate during the short campaign

….

Non-party campaigns must notify the Electoral Commission if they intend to spend more than £10,000 across the UK. They must register with the Commission and submit spending returns if they spend more than £20,000 in England or more than £10,000 in the devolved nations. Foreign entities cannot spend more than £700 (except groups of UK overseas electors).

Several spending limits are then applied to registered campaigns. These include limits on total spend in each nation, a limit on spending in each constituency (with certain national spending also allocated on a constituency level) and a limit on ‘targeted spending’ in support of a particular party or its candidates.

By contrast, for the US after the Citizens United ruling, in the 2024 presidential elections for example more than $1 billion was spent by dark money groups (up from less than $5 million in 2006). These groups are only required to report spending for certain activities, and in particular they’re not required to disclose donations to Super PACs. As the Brennan Center explains:

In the 2010 case Speechnow.org v. FEC, however, a federal appeals court ruled — applying logic from Citizens United — that outside groups could accept unlimited contributions from both individual donors and corporations as long as the groups don’t give directly to candidates. Labeled “super PACs,” these outside groups were still permitted to spend money on independently produced ads and on other communications that promote or attack specific candidates.

As we saw earlier, these changes to campaign finance laws were key to Musk’s influence on the 2024 election (which the Brennan Center explains at more length here )

Middle-Class Rent-Seeking

Economists use the term "rent-seeking" to describe efforts to increase one's share of existing wealth without creating new wealth (making others worse off).

Housing Restrictions

Perhaps the clearest example is housing policy. In both the US and UK, existing homeowners (predominantly middle and upper-middle class) have strong incentives to restrict new housing development:

Restrictive zoning laws maintain neighborhood "character" while conveniently preserving property values

Local control of land use gives existing residents veto power over new development

Environmental reviews and building regulations, while often well-intentioned, provide tools to block new housing

This transforms housing from a consumption good into an appreciating asset for the middle class, often at the expense of investment in more productive assets.

This has further effects on things like access to high quality schools.

Professional Licensing and Occupational Protection

Professional groups use licensing requirements and other barriers to entry to restrict competition:

The American Medical Association has historically limited the supply of doctors through restrictions on medical school slots and strict licensing requirements

State licensing boards, often dominated by existing practitioners, create elaborate requirements for entry into professions from hair braiding to interior design

Professional associations lobby for regulations that protect incumbents under the guise of consumer protection

The AMA's role in restricting healthcare supply is particularly well-documented. Twenty years ago, the AMA lobbied to reduce the number of medical schools, cap federal funding for residencies, and cut a quarter of all residency positions. While they've partially reversed course in recent years, they continue to lobby intensely against expanding scope of practice for non-physician providers, despite evidence that such restrictions don't improve care quality.

As another stark example, a woman named Sandy Meadows died in 2004 "alone and in poverty, because she could not get a license to work as a florist in Louisiana, the only state in the country to have such a nonsensical requirement." (Louisiana scrapped the licensing requirement for florists in 2024)

Research on the development of national health insurance in the post-World War II era found that the AMA financed a campaign against national health insurance that successfully shifted public opinion and increased private insurance enrollment. It suggests "the rise of private health insurance in the U.S. was not solely due to wartime wage freezes, collective bargaining, or favorable tax treatment," but was partly the result of interest group campaigning.

As data from OpenSecrets shows, the AMA was the the 7th largest lobbying spender in 2024 and the 5th largest considering all spending from 1998.

Further, regressive policies like student loan debt forgiveness derive support from college graduates, who are usually middle or upper-middle class by income, while those with the highest amounts of student loan debt are usually high income professionals like doctors, lawyers and MBAs. Similarly for policies like reduced use of standardized testing for college admissions

When a policy creates large benefits for a small, organized group and small costs for many unorganized individuals:

The beneficiaries have strong incentives to organize, lobby, and vote based on that issue

Those bearing the diffuse costs rarely organize in opposition

Politicians respond to the organized interest rather than the unorganized majority

This dynamic explains the persistence of policies like agricultural subsidies, trade protections, and occupational licensing requirements despite their overall inefficiency.

Case Study: UK Housing Crisis

The UK housing market exemplifies these principles in action:

Homeowners, who form a majority of voters in many constituencies, benefit from policies restricting housing supply and propping up house prices

Local planning authorities give existing residents substantial power to block development

Green belts around cities, while environmentally beneficial in some ways, severely restrict housing supply

Worker Cooperatives and Economic Constraints

Worker cooperatives—often championed as alternatives to traditional firms—face their own constraints. Economic analysis suggests that cooperatives may underhire relative to conventional firms, as existing members have little incentive to expand membership once profit-per-worker begins to decline, even if total profit would still increase and someone who would otherwise have no income could be productively hired.

This suggests that increasing the prevalence of worker cooperatives will lead to more people being unemployed.

Similarly, stronger employee rights in Europe that make it harder to fire workers mean firms are much more reluctant to hire. This partly explains Europe’s higher rate of youth unemployment compared to the US.

Stronger European labour protections, at least with respect to temporary contract work, can be seen as benefiting older/ more experienced workers at the expense of younger workers

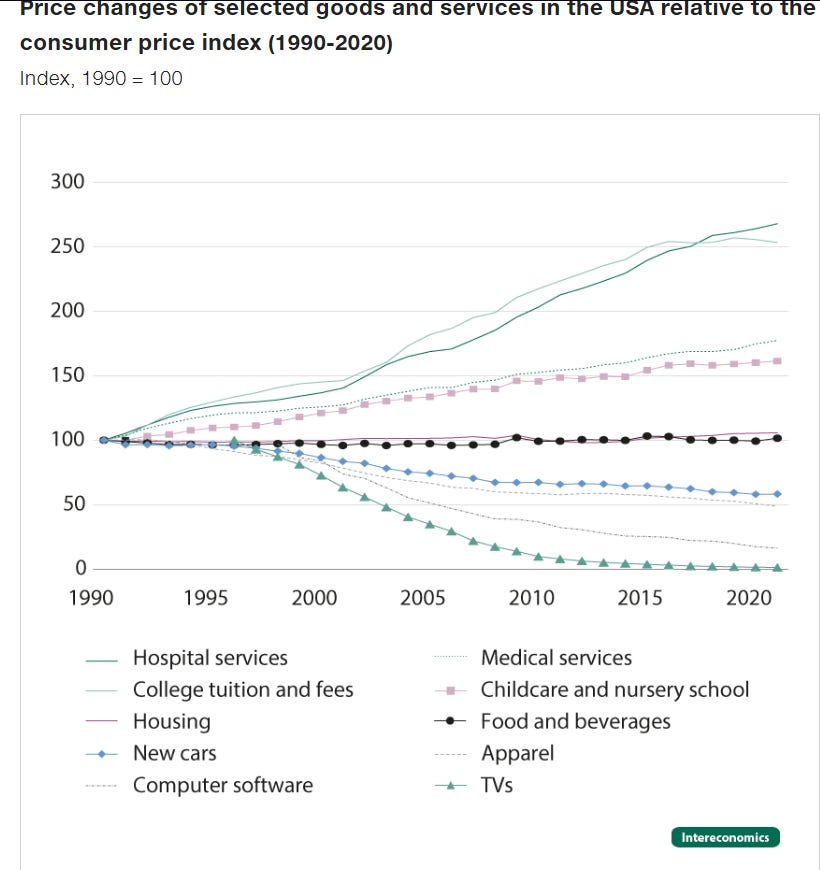

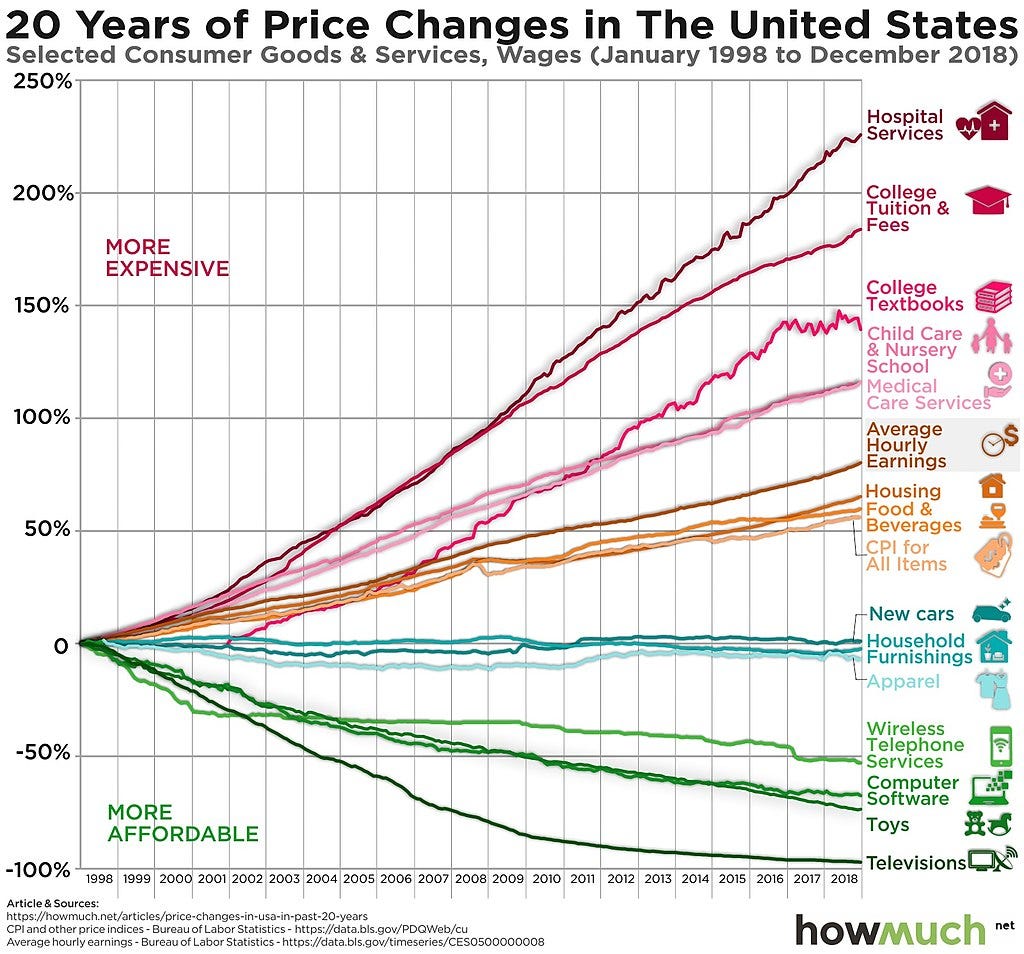

Cost Disease Politics: Why Crucial Services Keep Getting More Expensive

Sectors with low productivity growth experience rising costs relative to the rest of the economy.

The mechanism works as follows:

In some sectors (like manufacturing or technology), productivity increases dramatically over time—a worker today can produce far more goods per hour than decades ago

These productivity gains allow for higher wages in these high-productivity sectors

To compete for workers, sectors with slower productivity growth must also raise wages

But since productivity hasn't increased proportionally in these slower-growing sectors, higher wages must be passed on as higher prices

Baumol's classic example was a string quartet: It still takes four musicians the same amount of time to perform a piece as it did centuries ago—the productivity of classical musicians hasn't fundamentally changed. Yet their wages must rise to prevent them from entering other professions where productivity and wages have increased.

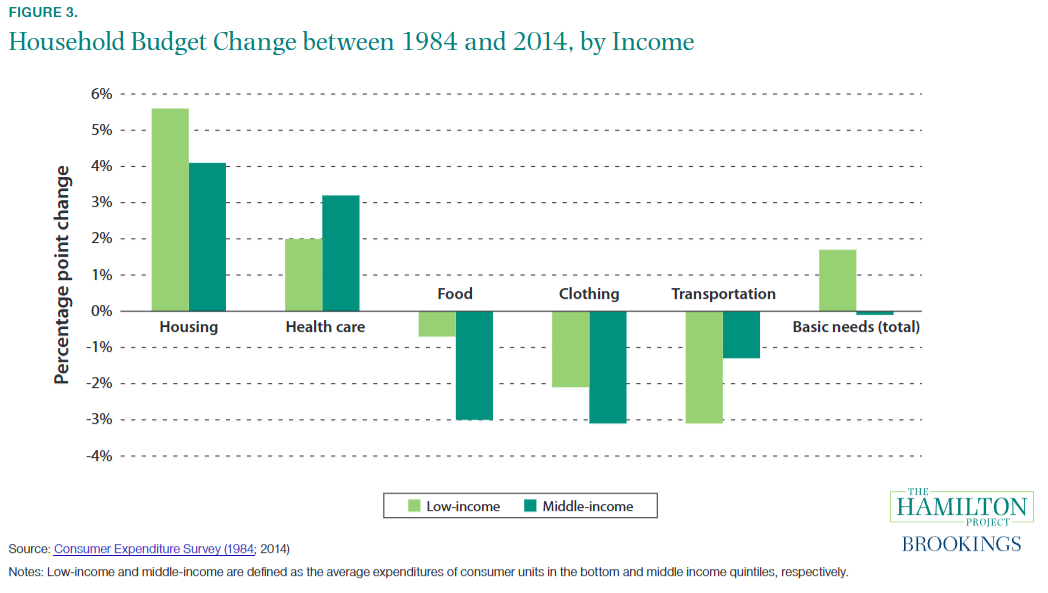

Healthcare and housing—these essential services consistently consume a growing share of both household budgets and government spending in advanced economies like the US and UK.

The Cost-Disease Sectors

Healthcare

A doctor might still treat only one patient per hour for certain conditions, just as decades ago. But their wages must rise to prevent them from entering other high-paying fields where productivity has increased. Since the number of patients treated per hour hasn't increased proportionally, this wage growth translates directly into higher healthcare costs.

Education

Similarly, while some aspects of education have become more efficient, the core model of teachers working with groups of students remains labor-intensive. Teacher salaries must rise to remain competitive with other professions, but class sizes haven't increased proportionally, driving up per-student costs.

Housing Construction

While some building technologies have improved, construction remains labor-intensive, with limited productivity growth compared to manufacturing. Rising wages in construction therefore drive up housing costs.

Childcare

Personal care services are perhaps the quintessential cost-disease sectors—one caregiver can only effectively care for a limited number of children , making productivity gains extremely difficult.

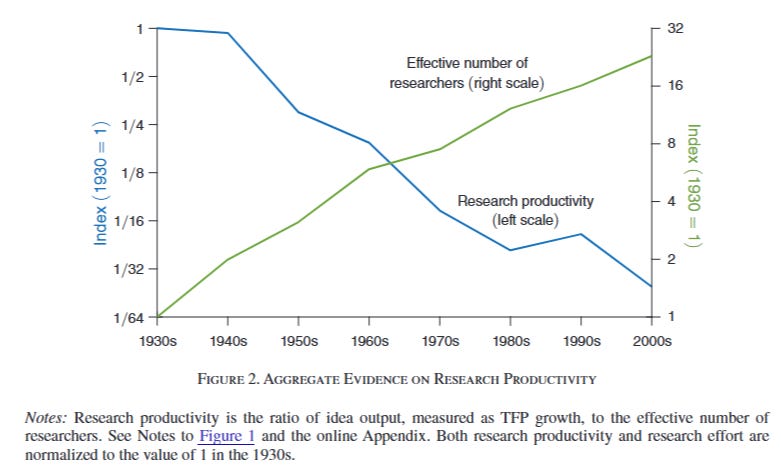

Ideas are getting harder to find

Research by Bloom, Jones, Van Reenen, and Webb titled "Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find?" documents that research productivity is declining sharply across various industries while research effort is rising substantially.

Their findings show, for example, "the number of researchers required today to achieve the famous doubling of computer chip density is more than 18 times larger than the number required in the early 1970s." They conclude, "everywhere we look we find that ideas, and the exponential growth they imply, are getting harder to find."

Similarly Patrick Collision and Michael Nielsen find that science is becoming less efficient on a per-person or per-dollar basis.

This matters because the fundamental source of rising productivity and living standards is R&D driven innovation and technological progress that produces useful productivity-enhancing ideas and techniques that can be replicated throughout the economy at negligible marginal cost.

This means technological solutions to cost disease may be increasingly difficult to develop, requiring greater investment in research and development just to maintain historical rates of progress.

As cost-disease sectors consume a growing share of GDP, societies face difficult choices about financing:

Private Financing: If these services remain primarily privately funded, they become increasingly unaffordable for average citizens

Public Financing: If government assumes these costs, tax burdens must rise or deficits increase

Rationing: Alternatively, access to these services must be limited in some way

Policymakers face painful tradeoffs between:

Maintaining service quality while accepting rising costs

Controlling costs while potentially sacrificing quality or access

Funding research into technological innovations that can break the tradeoff

The Generational Dimension

Healthcare and elder care costs rise with an aging population, and are passed through to younger workers via taxes

Housing becomes increasingly unaffordable for younger generations, while appreciating house prices make houses a key retirement asset for homeowners.

Educational costs shift either to government budgets or student debt

Case Study: UK's NHS Crisis

Healthcare costs rise faster than general inflation due to Baumol effects

An aging population increases demand for healthcare

The government faces pressure to limit tax increases on workers

The result is a perpetual sense of crisis despite increasing funding

Every UK government promises NHS reform, but the fundamental economic constraints remain unchanged regardless of which party holds power.

Case Study: US Higher Education

Labor-intensive teaching models drive rising costs

Competition for prestige leads to amenity wars and administrative bloat

Government subsidies and loans ease affordability concerns in the short term but enable further cost increases

Students face growing debt burdens while the system resists fundamental change

However, note that not all of the increase in college tuition can be attributed to Baumol’s cost disease. Gordon and Hedlund find “ ..that demand-side theories—namely, the role of financial aid expansions and the rise in the college premium—generate the strongest effects“

Genuine productivity improvements through technology might be our best hope for breaking the cost disease cycle:

Telemedicine allowing one doctor to treat more patients

Educational technology enabling more personalized learning with fewer instructor hours

Modular construction techniques reducing labor needs in housing

Developing innovative technology often requires substantial investment with uncertain long term returns that don’t fit within the timescale of the election cycle, and which mostly benefit future citizens (as opposed to current voters who must pay for the investment).

In general, innovators do not capture most of the social gains from their innovations, so government funding is required to internalize that externality.

However that funding will not necessarily generate returns for the taxpayers in the present who must pay for it.

Removing artificial constraints on productivity can help:

Allowing nurse practitioners and physician assistants to perform more medical tasks

Reforming zoning to enable more efficient housing construction

The Geography of Discontent: Place-Based Inequality and Political Divides

Brexit votes split dramatically between thriving urban centers and struggling post-industrial regions. Similarly, US presidential elections increasingly map onto distinctive regional economic patterns. These spatial divides reflect economic transformations that have concentrated opportunity in specific places while arguably leaving others behind.

The Great Agglomeration

Superstar cities like London, New York, and San Francisco pulled ahead economically

Former industrial regions increasingly fell behind

Rural areas faced persistent economic challenges and population decline

This divergence has created "left behind" places—communities experiencing economic stagnation, population loss, and diminishing prospects.

The Knowledge Economy and Geographic Sorting

This regional divergence stems largely from structural economic changes:

The transition from manufacturing to knowledge-based industries

Increasing returns to education and specialized skills

The growing importance of agglomeration effects—the benefits firms and workers gain from proximity to others in their field (though there is some recent debate about the magnitude of this effect)

While the "China Shock" of increased trade competition has received significant attention, particularly in the US context, research suggests deindustrialization has multiple causes. Beyond international trade, automation, interstate competition, and broader structural transformation toward service economies have all played important roles.

These trends concentrate economic opportunity in cities with existing advantages—universities, cultural amenities, and networks of innovative firms. Meanwhile, places historically dependent on manufacturing or resource extraction struggle

The Role of Housing Markets

As economic activity concentrates in superstar cities, housing restrictions prevent the population adjustments that would naturally address regional inequality. Middle-class homeowners in thriving regions block development that would allow others to access opportunity

This artificial supply restriction drives up housing costs in productive areas, preventing many workers from relocating to where their skills would be most productive :

We calculate that this increased wage dispersion lowered aggregate U.S. GDP by 13.5%. Most of the loss was likely caused by increased constraints to housing supply in high productivity cities like New York, San Francisco and San Jose. Lowering regulatory constraints in these cities to the level of the median city would expand their workforce and increase U.S. GDP by 9.5%. We conclude that the aggregate gains in output and welfare from spatial reallocation of labor are likely to be substantial in the U.S., and that a major impediment to a more efficient spatial allocation of labor are housing supply constraints. These constraints limit the number of US workers who have access to the most productive of American cities. In general equilibrium, this lowers income and welfare of all US workers.

These issues with the housing market have been linked to a variety of other problems like inequality, fertility and obesity in what is known as the Housing Theory of Everything

Electoral Systems and Geographic Power

The US and UK use first-past-the-post voting systems with single-member districts that give places political representation regardless of population size. This means:

Declining regions retain political power even as their populations shrink

Urban areas with growing populations become increasingly underrepresented

Geographic interests gain priority over total vote shares

These systems create strong incentives for politicians to cater to place-based interests rather than national majorities.

The Politics of Place

Voters in declining regions may support policies that promise to restore local prosperity, even if those policies seem economically inefficient from a national perspective.

Duverger’s Law and Two-Party Rule

Duverger’s law is the claim that in electoral systems like the US and Britain with single-member districts and first-past-the-post voting, only 2 political parties will be tend to be in power

Small parties with support spread thinly across many districts will struggle to win any seats while similarly sized parties with high rates of support in just a few districts will not.

Given two large parties, any third parties tend to divert more votes from the party it is most similar to, leaving the other party with a plurality.

Duverger presents the example of an election in which 100,000 moderate voters and 80,000 radical voters are to vote for candidates for a single seat or office. If two moderate parties and one radical party ran candidates, and every voter voted, the radical candidate would tend to win unless one of the moderate candidates gathered fewer than 20,000 votes. Appreciating this risk, moderate voters would be inclined to vote for the moderate candidate they deemed likely to gain more votes, with the goal of defeating the radical candidate. To win, then, either the two moderate parties must merge, or one moderate party must fail, as the voters gravitate to the two strongest parties. Duverger called this trend polarization

We see this play out in UK general elections, where often third parties win a large vote share but do not win proportionately many seats because their support is geographically spread out, and where the entrance of a third party similar to an existing party can tank the electoral success of both. This means that while some regions are structurally overrepresented in terms of seats per vote, any political factions in those regions must work through (or displace) one of two dominant parties in their region

As The Economist, commenting on vote-splitting between the Conservatives and Reform in 2024 elections, notes:

This lesson will take some time for right-wingers to learn. They will cling to comforting factoids, much as their progressive foes did. Did you know that, combined, the Conservative and Reform vote would have pipped Labour’s puny haul? Well, in the 1980s the combined vote share of Labour and the Social Democratic Party, a more moderate spin-off, comfortably outstripped that of Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Party. That did not stop Thatcher wrenching the country to her will. It is little more than the psephological equivalent of: “If my mother had wheels, she would be a bike.”

Case Study: Brexit and the UK's Regional Divides

The 2016 Brexit vote provides a clear example of some of these dynamics:

Strong "Leave" votes came from post-industrial towns, coastal communities, and rural areas

Strong "Remain" votes concentrated in London, university towns, and prosperous regional centers

Research shows these voting patterns correlate with indicators of economic decline and demographic change rather than simply reflecting pre-existing political preferences.

Case Study: America's Geographic Polarization

Similar patterns appear in US politics:

Democratic support increasingly concentrates in major metropolitan areas and their suburbs

Republican strength grows in rural and small-town America

Former industrial regions show complex, often volatile voting patterns

However for the US, this is more an effect of region than rurality per se (people living in the South and West are more likely to vote Republican than individuals living in the North, for example, with little independent influence of rurality)

Identity and Geographic Politics

Recent research on identity politics provides further insight into these geographic divides. A study by Gennaioli and Tabellini examines how dimensions of political polarization have shifted from class to cultural identity, finding evidence that economic shocks like the "China Shock" (which reallocated employment from manufacturing to services in some regions while simply decreasing manufacturing employment in others, depending on the share of the residents with a college degree; a proxy for human capital) contributed to this realignment. Their work suggests that "parties that compete on policy and spread stereotypes to persuade voters" can drive identity-based polarization that reconfigures political coalitions.

The Geographic Policy Trilemma

Policymakers addressing geographic inequality might face a trilemma—they can pursue at most two of these three goals:

Economic efficiency: Allowing resources to flow to their most productive uses and locations

Geographic equity: Ensuring prosperity is widely shared across regions

Limited government: Maintaining relatively low taxes and minimal intervention

Solutions and Tradeoffs

Place-Based Policies

Targeted investments in struggling regions can help revitalize local economies:

Enterprise zones with tax incentives for business location

Infrastructure investments connecting isolated areas to economic centers

Educational investments to build human capital

The effectiveness of educational investments is constrained by the cost disease dynamics discussed previously.

Andrew Garin in Do Place-Based Industrial Interventions Help "Left-Behind" Workers? Lessons from WWII and Beyond also finds

While government plant construction during WWII drove an expansion of high-wage semi-skilled jobs open to local residents, which in turn fueled an increase in upward mobility among local residents, the evidence from more recent interventions suggests that modern plant sitings often fail to yield similar benefits to local workers. The implementation details of industrial interventions matter crucially for their incidence on local workers. Interventions that generate opportunities for up-skilling and occupational advancement accessible to target populations appear to be most likely to generate meaningful distributional benefits. I argue that while core production goals during WWII happened to inherently align with the promotion of upward mobility, such alignment is not guaranteed in general and may be the exception rather than the rule in modern contexts.

People-Based Policies

Alternatively, policies can focus on helping people rather than places:

Relocation assistance to help workers move to opportunity

Education and training programs to build transferable skills

Strong safety nets that follow individuals regardless of location

These approaches may be more economically efficient but can accelerate population decline in struggling regions. They also face political obstacles from the electoral systems mentioned earlier, which give disproportionate power to places regardless of population (since they can exacerbate declining support among those who remain in the depopulating regions for parties that implement those policies).

Conclusion

The political systems of the US and UK are increasingly shaped by overlapping structural constraints: aging populations raise dependency ratios and entitlement costs; cost-disease sectors like healthcare and education absorb growing fiscal space; housing and occupational restrictions, often driven by middle-class interests, inhibit productive investment and social mobility; geographic divergence entrenches spatial inequality while distorting representation; and electoral institutions give economically stagnant regions political power disproportionate to their population.

These dynamics are not isolated—they reinforce one another. Aging voters oppose immigration and entitlement reform; middle-class incumbents block housing growth and licensing liberalization; declining regions retain political leverage disproportionate to their economic role. Democratic institutions, designed to mediate interest group competition, increasingly channel it into distributive rigidity.

What emerges is a political economy where each group’s preferences are rational in isolation but collectively self-defeating. Entitlements rise while public investment stalls. Productivity-enhancing reforms exist on paper but are politically infeasible. The political median is pulled toward preserving the status quo, even as that status quo generates long-run stagnation.

Crucially, this drift is not just the result of policy error or elite overreach, but of the internal logic of democratic competition under current demographic and institutional conditions. The costs are not just fiscal, but developmental—sustained underinvestment in future-facing goods like housing, infrastructure, education, and research risks compounding inefficiencies over time.

Even when reforms can be attempted—child allowances, fertility incentives, regional industrial policy—the returns are increasingly modest or require levels of investment difficult to justify within electoral cycles. Meanwhile, underlying productivity growth slows, and innovations become harder to find. Political systems are thus asked to do more with less—while increasingly organized around distributing what already exists.

Absent institutional reform, the path of least resistance remains a slow reallocation of public resources from younger to older voters, from all workers to credentialed insiders, from future productivity to present consumption. The outcome is a politics that remains procedurally democratic and functional but substantively misaligned with long-run societal needs.

The problem isn’t that no one knows what to do—it’s that almost every path forward is blocked by someone who votes.